Puerto Rican folklore

Afro-Cuban traditional music

African-American soul and funk

African-American experimental jazz

Eddie Palmieri

Grupo Folklórico y Experimental Neoyorkino

Latin Jazz

Like Jerry and Andy González's projects, such as Ft. Apache Band, and many others.

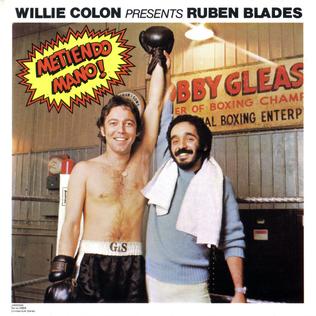

Salsa was, among the things, a nationalist movement, as illustrated in the Fania film, Our Latin Thing (Cosa nuestra)

People have been, and still are playing rumba in the parks of New York.

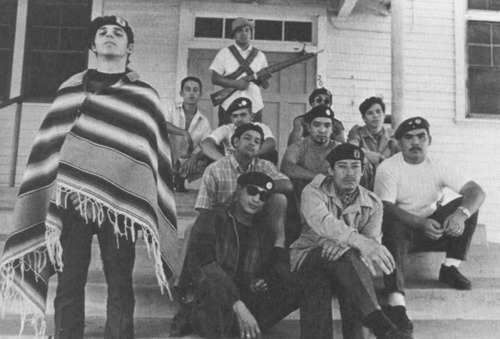

The Young Lords

The Young Lords, whose 13 Point Plan included rights for US Puerto Ricans, the independence of the island of Puerto Rico, women's liberation, and solidarity with the Vietnamese people, began in Chicago in 1967, spread to New York (and beyond) in 1969, and was influential until the mid 1970s.

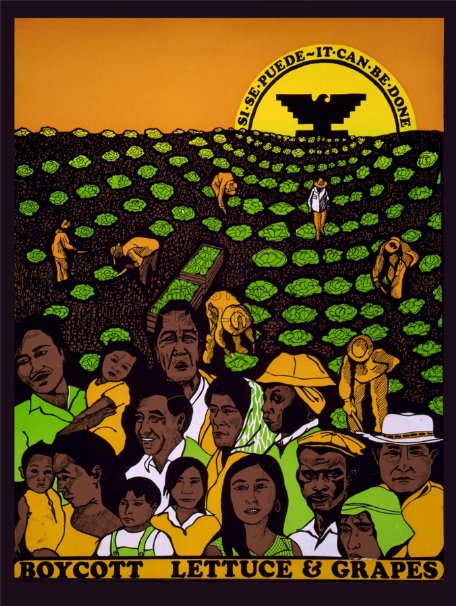

The Chicano movement was a confluence of related struggles: an assimilationist Mexican-American movement that sought equal rights of citizenship and political representation; a labor movement organized around Mexican-American (and to some extent, Asian-American) farmworkers; a student movement that organized against the Vietnam War, police discrimination and brutality, equality of education, and negative stereotypes of Latinos in the popular media; and a nationalist movement organized around the idea of creating an independent and territorially defined nation.

The Chicano movement had political, artistic, and of course musical ramifications. Those musical ramifications were varied, but in general they can be described as passing from a very ambiguous acknowledgement of their ethnicity to a much more straightforward racial pride.

Another important stream was the rock and Afro-Cuban fusion pioneered by Santana. The path is more circuitous than it might seem. Carlos Santana was born in Mexico and grew up playing mariachi music. But he hated that music and was much more inspired by blues and rock in the multi-racial band he led when he moved to San Francisco. Afro-Cuban slowly began to come in with Mike Carabelo, a high school friend of Santana's who had picked up congas in drum circles, and especially from San Francisco club owner and rock impresario Phil Graham, a transpalnted New Yorker (Born Jewish in Germany and escaping right before World War II) who had grown up dancing in the Palladium. Santana played at the legendary Woodstock festival, to tremendous acclaim, especially when the Woodstock film came out.

This model, of Chicanos playing Afro-Cuban-tinged rock was influential for many bands, such as El Chicano, which, despite largely ignoring actual Mexican music, was quite political and up-front about being Chicanos.

Later, Los Lobos, of L.A., started experimenting with traditional Mexican music, and even put it into their cover of Valens' "La Bamba" for the movie of the same name - note the trad jarocho breakdown at the end of the song (2:20). Country-rocker Linda Ronstadt, a multi-platinum-selling artist who was the best known and best paid woman in the msuic industry during her heyday in the 1970s, and who had never highlighted being an Arizona Chicana, did an all-mariachi album called "Canciones para mi padre/Songs for My Father" in 1987, and two more albums of Mexican music in the early 1990s.