Many of the industrial songwriters of Tin Pan Alley's Brill Building were Jewish mambo-niks who frequented the Palladium a few blocks up Broadway.

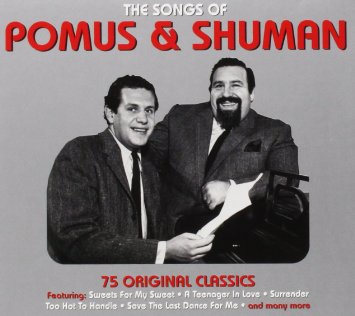

Mamboniks like Doc Pomus and Mort Schuman penned a number of songs with a significant (if not necessarily "authentic") Cuban feel for the mostly African-American R&B act they worked with: Pomys even called these songs: "Jewish Latin."

Check out the underlying habanera rhythm (or similarly asymmetrical variants) in The Ronettes' "Be My Baby" (1963), The Drifters' (güiro-filled) "Under the Boardwalk" (1964), Ben E. King's "Stand by Me" (1960/61, from the same recording session as King's "Spanish Harlem"). These same songs are filled with castanets, güiros, maracas, and other Latinoid signifiers. The bassline would stick around long enough and be whitened enough to be used by Fleetwood Mac in "Dreams" (1977).

Three-chord Cuban songs formed another musical cell used in much music in the 1960s: "Caramelo" by the Sonora Matancera (with Celia Cruz singing) was repurposed as "Good Lovin'," first by an African-American group, the Olympics (1965), then a best-selling rock cover by The Rascals (1966). Another, slower, version of the three-chord Cuban son shows up in the Isley Brothers' "Twist and Shout" (1961) and the McCoys' "Hang on Sloopy" (1965). (This last song was later, strangely, covered by the seminal Cuban son pioneer Arsenio Rodríguez in 1966). All of this was with the involvement of Brill Building mambonik Bert Berns, whose music all had some degree of Cuban feel.

Bolero, that old staple of the Rhumba Era Latunes, would also play a part in many rock musicians' more romantic repertoire. Elvis, of course, but also the Beatles.

New Orleans Rock Tresillo and African-American Latin

Black musicians were also very into the maraca. Chuck Berry (of "Johnny B. Goode") used maracas in his first hit "Maybellene" (1955)...

... and Bo Diddley's "Bo Diddley" (1955) not only has maracas but is also a straight up son clave rhythm.

Finally, it's worth mentioning the ways in which funk used then Afro-Caribbean concept of dividing up simple rhythmic parts between different instruments to make complex rhythmic textures, as in James Brown's "Say It Loud (I'm Black and I'm Proud)," which also features a break using son clave at 1:35 and 2:32.

The Latinish feel was also taken up by black-owned commercial music as well, as in Motown. Listen for the conga break in this Tempations tune:

No comments:

Post a Comment