African-derived music in Cuba. Ritual drumming and Yoruba-language song in the Santería or Regla de Ochá religion. (This example is from New York, where the Cuban master drummers Román Díaz and Pedrito Martínez live).

Neo-African secular (non-religious) music, with clear relation to African musics but created in the Caribbean. Here, the Afro-Puerto Rican music called bomba in the town of Loiza, PR. Bomba, too, is practiced in the United States today by stateside Puerto Ricans.

These kinds of music circulated throughout the Caribbean, crossing national and linguistic lines. Compare the previous video of Puerto Rican bomba with gwoka from the French island territory of Guadeloupe.

Also compare with this 1800s artist's conception of dances in Congo Square in New Orleans, where, unlike in the rest if the US, drumming was permitted until 1845 (Manuel 11).

This continues to be reflected in some New Orleans practices like Mardi Gras Indians and second line

Awesome polyrhythm (rhythms that have more than one pulse, so you can tap your feet to or clap to the same rhythm in different ways). This is the Afro-Cuban religious music called güiro. The timeline, tapped on a metal implement has 12 beats, but the instrument in the middle plays 4 beats over it. You could just as easily clap it in 3.

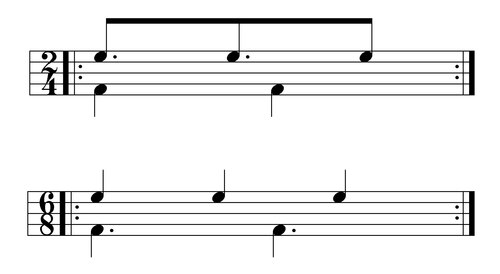

Here are some of the central rhythms in Afro-Caribbean music. They're all represented here repeated once.

Straight, un-syncopated 4/4 pulse

2+2+2+2

X . X . X . X . / X . X . X . X .

Tresillo

3+3+2

X . . X . . X . / X . . X . . X .

Cinquillo

2+1+2+1+2

X . X X . X X ./ X . X X . X X .

(Note that this is basically the tresillo with two extra beats

X.xX.xX. / X.xX.xX.)

Habanera

3+1+2+2

X . . X X . X . / X . . X X . X .

(Note that this is basically the tresillo on top of the 1 and 3 of a straight 4/4.

X . . X . . X .

X . . . X. . .)

Many of these rhythms are still important in music from the Spanish- and English-speaking Caribbean, as well as African-American music today.

It's worth noting that African-American music here in the US has long had some syncopated tresillo-like motifs in the cakewalk, ragtime, charleston, and other genres. This sometimes sounds like a tresillo without the last beat, as in the Charleston: 3+5 or X . . . X . . . .

Creolization

The process of creolization often produced unexpected results, as in the encounter of neo-African music and neo-European dance in the Haitian-influenced "Tumba Francesa" of eastern Cuba. Again, note the persistent cinquillo being tapped out with drumsticks on a wooden surface.

Much Caribbean salon music has these rhythmic cells under an elegant European façade, as in Puerto Rican danza, such as "Margarita" by Manuel Tavárez (1843-1883).Notice the faint cinquillo rhythm in the background. Sometimes it alternates with a straight 1-2-3-4.

Even more creolized was the Cuban danzón. This piece was the first recorded danzón, "Las alturas de Simpson" by Manuel Failde, from 1879 - pretty much a cinquillo-fest.

Compare with the Cuban danzón bands of the time.

The habanera rhythm became popular worldwide, particularly in Spain, Argentina (tango), Brazil (maxixe), and Mexico. For his 1875 opera Carmen, set in Spain, French composer Georges Bizet composed perhaps the most enduringly famous habanera, "Love is a rebellious bird," here sung by the great María Callas.

Bizet's habanera was borrowed from a composition by the Spaniard Sebastián Yradier called "La paloma." Yradier himself borrowed the habanera from the music he had heard while stationed in Cuba (then under Spanish rule) in the late 1850s.

Yradier's 1859 composition "La Paloma"b was brought to New Orleans to great acclaim by the band of the Eigth Regiment of Cavalry of the Mexican Army, a large military band which held a long residency in the Crescent City during the World's Fair of 1884-85. They also sold a good deal of sheet music including their repertoire of habaneras, danzas, contradanzas, danzones, and other Cuban and Caribbean pieces. "La Paloma" remains popular today. Here's one recording from 1928 by the soprano Amelita Galli-Curci.

Or, better yet, the seminal New Orleans pianist and bandleader Jelly Roll Morton (1890-1941) illustrating the “Spanish tinge” himself:

By the turn of the 20th century, the habanera was all over the African-American popular music called ragtime. (Ragtime explained here). The most famous ragtime today is probably Scott Joplin’s “Maple Leaf Rag,” made famous again by the 1970a movie The Sting and ice cream trucks across the nation. Joplin likley picked up ragtime at the Chicago World's Fair in 1893. Chicago was connected by river and rail trade with New Orleans. Notice how the melody shifts from the rag syncopation to the habanera at the end of the line.

Scott Joplin’s “Solace (Mexican Serenade)” – notice the habanera rhythm

Here's “The Dream” by Jesse Pickett (a roving pianist active in Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York), played by Eubie Blake, (who was born in 1887 in Baltimore) - neither were New Orleanians or Missourians, but from the East COast, which shows how fast the rhythm became popular.

St, Louis composer W.C. Handy starting incorporating the habanera in his music as a deliberate effect. His famous St. Louis Blues (1911) is a "tango-blues" – find which section is the tango (that is, using the habanera) and which is the blues:

W.H. Tyers’ “Maori (A Samoan Dance)” (1908) – find the habanera:

No comments:

Post a Comment